/ magazine

| Simon Faulkner | 2008-10-22 17:31:20 |

Testing the binaries between politics and aesthetics, lens-based media and painting, and political relevance and irrelevance.

Within Israel David Reeb has often been considered a political artist. This opinion is held despite the fact that much of his artistic production has involved abstract paintings, still-lives, and images of his domestic life in Tel Aviv. This is also an appraisal of Reeb’s work that does not take into account his equivocal attitude towards the idea of political art, an attitude expressed in his comment, made in 1997, that: ‘I’m not representing a situation, I’m not representing anyone, I’m barely representing myself.’ Paintings that have been taken as straightforward political statements have often been much more ambiguous representations that foreground the problematical nature of relationships between art and political reality. Many of Reeb’s paintings judged to be political were worked from press photographs of events related to the occupation of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. These paintings address the subject of the occupation through their source material, while at the same time presenting painterly images that are doubly removed from the events depicted in the original photographs. Such works stage the problematic of the relationship between art and politics without necessarily providing a solution. As such, they can be linked to Jacques Ranciére’s observation that ‘there is no criterion for establishing a correspondence between aesthetic virtue and political virtue.’ Reeb’s paintings from press photographs imply an interest in finding such a correspondence, but at the same time attest to a sense that a connection between art and politics is in no way obvious.

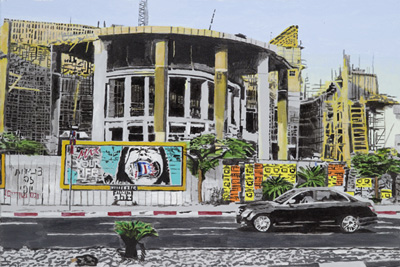

Habima, David Reeb, 2007-2008 (acrylic on canvas)

It has been a strength of Reeb’s art in the past that he has refused a straightforward answer to the question of what a political art might be, choosing instead to ruminate upon the place of painting as a form of mediation between the viewer in the gallery and other realities. Sometimes he has done this by treating his paintings as kinds of screen. An example of this is Let’s Have Another War#8 (1997), a painting partly derived from a Miki Kratsman photograph of the Tunnel War in Ramallah in September 1996. Reeb transcribed this photographic image into paint on canvas, but then overlaid parts of the resulting picture with flat abstract motifs. The artist has described this effect as a process through which ‘the photographic pictures … underwent additional transformations [and] eventually became a screen, a veil.’ He has also referred to such works in relation to a desire to deal with paintings ‘as a kind of barrier’. This process of screening or veiling can be understood in terms of a contest played out upon the surface of the painting between different pictorial elements and meanings. On the one hand there are iconic elements derived from the photographic image that point to the political conditions of the occupation, however distanced by their double mediation, while on the other there are abstract elements that refer to notions of artistic autonomy. Other paintings from the late 1990s address this division of the political from the aesthetic in different ways. All the Colors of the Rainbow (1997) presented an image of Israeli tanks in Ramallah during the Tunnel War above an image of a Henry Moore sculpture in the grounds of the Israel Museum, thus setting up a contrast between a peaceful space of high culture and a space of violent political conflict. These two images were separated by a horizontal black line that not only suggested the distancing of brute politics from aesthetic concerns, but also the stark difference between the lives of most Israelis within the Green Line and Palestinians under occupation.

The paintings Reeb has made in 2008 of demonstrations against the West Bank Barrier in the Palestinian village of Bil’in, on display at the Artist’s House in Tel Aviv, constitute a departure from these longstanding concerns with the problem of political art, and with the division between the Israeli viewer and aspects of political reality. Instead of focusing on the mediation or screening of these realities, the paintings of Bil’in appear to result from a desire to produce more direct pictorial representations of the occupation. This shift within Reeb’s practice is in part defined by a technical change in the way his paintings are made. The earlier paintings of photographs involved the projection of a photographic image onto a canvas, enabling its rapid tracing in paint. These paintings would usually be made in one session and often involved the application of one layer of paint. The production process for the paintings of Bil’in is more complex, involving an initial stage of projection and tracing, followed by a further stage in which Reeb continues to work on the painting, layering the paint and adapting the original image. These paintings are taken beyond the status of being a painterly trace of a photographic image to a point where the painting gains an independence from its pictorial source. This independence is defined by a sense that the paintings involve a search for a connection with political reality through a kind of documentary realism that draws them away from the acts of appropriation and pastiche involved in much of Reeb’s earlier work.

Hyrax, David Reeb, 2007-2008 (acrylic on canvas)

This documentary aspect is also present in the paintings Reeb produced, and currently shown, alongside those depicting events in Bil’in. Paintings of the valley of Klil, Yechiel Shemi sculptures amongst cactuses at Kibbutz Cabri, the forecourt of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, and the Habima Theatre under reconstruction. Within the context of the exhibition the contrast between the scenes in these paintings and those of Bil’in is as stark as the contrast presented in All the Colors of the Rainbow. A sunlit landscape can be set against barbed wire and tear gas; places of culture - despite temporary ruination in the case of the theatre, the army base in the scene in front of the Tel Aviv Art Museum, and the cactuses at Cabri suggesting the former presence of a Palestinian village – can be set against scenes of violent confrontation and anger. Here the divisions between art and politics, and between Israel and Palestine come back, but not in the form of a reflexive meditation on the condition of painting. Instead these paintings function much more directly as attempts to render the different sights Reeb has been encountering in his life: in Tel Aviv, in the north of Israel and the West Bank. The camera lens still plays a significant part in the process of making paintings. After all, on his website Reeb has called one of his paintings Clil from Photo #1. Yet the emphasis here does not appear to be so much upon the painting of a photograph as an already existing image/object, but on the use of the photograph as a point of departure for the rendering of a separate image that has a stronger relationship to phenomenological experience. With this in mind, the paintings of Klil worked from photographs can be related to those paintings Reeb made from observation in the same area in 2007, a number of which are also on display in the Artist’s House. It seems that the experience of painting the landscape of Klil on the spot, finding painterly equivalents for phenomena directly witnessed, has influenced the ways that Reeb further adapted the images of Klil initially traced through the projection of photographs.

Hand, David Reeb, 2007-2008 (acrylic on canvas)

This change in approach seems to have also been enabled by Reeb’s experience of making videos of the demonstrations at Bil’in, a practice that has allowed him a direct engagement with the conditions of the occupation. The lens-based image has become something enmeshed with physical acts and decisions made by the artist in the heat of demonstrations that often involve violent responses on the part of soldiers, rather than something appropriated from photographers who have been the ones visiting sites of conflict. Frame-grabs from his videos of the demonstrations have functioned as starting points for particular paintings, but Reeb’s acts of video making in Bil’in do not simply have a relationship to his paintings as source material. By referring to his experiences on the ground, Reeb seems to have sought some way around the division between the painterly and the political.

This has not meant that Reeb’s awareness of the complexities of artistic production and of the problematical nature of trying to make art serve political advocacy has disappeared. The Bil’in paintings may have been produced out of a desire to engage with a reality that Reeb has experienced as a political participant, however his own discussion of the paintings suggests that they continue to be haunted by reservations about the possibilities of painterly realism and for an art that can be seen as political. In a sense the paintings of Bil’in involve a temporary suspension of disbelief in these possibilities. Yet this disbelief – the understanding, in Reeb’s own words, that it is ‘difficult to do the idea of political painting’ – remains a condition in relation to which the Bil’in paintings are defined. In a recent statement Reeb observed:

About four years ago I started using a video camera for my work. Landscape painting was a change for me, different from habit. When I studied art, the convention was conceptual, not landscapes. And to paint something with a kind of documentary aspect, that’s even more than painting a landscape. To me it’s not self-evident. On video I document people and events whose meaning is greater than that of painting. It’s a way of stepping outside yourself. When I videotape at protests, there are more important things than the work of painting, than the artistic aspects.

These comments suggest that the paintings of Bil’in involve a new kind of subject matter for Reeb that combines landscape painting with a realist concern to document the effects of the West Bank Barrier. But the statement also suggests that these paintings need to be differentiated from his video work and that the latter are more directly political and thus of a different kind of moral significance. At work in this statement are a set of binaries that divide between politics and aesthetics, lens-based media and painting, and political relevance and irrelevance. Yet the relationships between Reeb’s video work and his painting seem to be more complex than this. The ‘stepping outside yourself’ enabled by the making of the videos in Bil’in has allowed an opening up of possibilities for new kinds of painting. What these paintings do and mean is not simple or ‘self-evident’, as Reeb observes, but they suggest that he is testing the binaries listed above in a different and promising way.

Parade, David Reeb, 2007-2008 (acrylic on canvas)

In these new paintings of Bil’in the subject of screening is still present, but now the screen is the West Bank Barrier itself. Screening effects occur within the paintings where barbed wire or a concrete wall set up to protect soldiers from rock throwing demonstrators block the view of the sky or a landscape. Such screening motifs refer to the literal ways in which the barrier denies unhampered viewing of the landscape of Palestine. They might also function as metaphors for the way that the Barrier symbolically screens off the plight of the Palestinians and the way that it stands as a denial of political vision. Through his use of the Barrier as a motif Reeb seems to have re-inflected a trope within his work that once signified a sense of disconnection between his artistic practice and his political views towards a more purposeful, though not unequivocal, political expression.

Dir Kadis, David Reeb, 2007-2008 (acrylic on canvas)

The exhibition- paintings by David Reeb, 2007-2008- will be on at the Artists House at 9 Elharizi st, Tel Aviv from the 25th October to the 18th November 2008.

- ‘”A painting is a thin layer of paint applied onto canvas”: Ariella Azoulay in conversation with David Reeb’, in David Reeb: Let’s have another war, Tel Aviv: M Publishers, 1997, unpaginated.

- Jacques Ranciére, The Politics of Aesthetics, London and New York: Continuum, p. 61.

- ‘”A painting is a thin layer of paint applied onto canvas”. Conversation between Simon Faulkner and David Reeb, Tel Aviv, 12 November 2007.

- Conversation between Simon Faulkner and David Reeb, Tel Aviv, 26 July 1999.

- Amira Hass, ‘About a Boy’, Ha’aretz, 5 September 2008.

www.bilin-village.org/english/articles/press-and-independent-media/About-a-boy